When I was five years old, my father became a born-again Christian. It’s not a time I like to remember, because my father embraced a form of evangelicalism which taught that men were ordained by God to be head of the household and that women were inferior. Like many evangelical women, I was taught not to question my father’s actions, which in my case included being sent to a private Christian school that taught that America was founded as a Christian nation and that most enslavers were kind, where I was once beaten for forgetting to wear a slip, because girls were only allowed to wear dresses. When I began to openly challenge my father’s rules, he sent me to a Christian nationalist reform school in the Dominican Republic.

Unfortunately, my experience is not unique. Thousands of evangelicals were abused in the name of religion. Journalist Sarah Stankorb interviewed women like me, women who were conditioned to believe that submitting to men was God’s will, yet grew up to question their abusers in her recent book DISOBEDIENT WOMEN: How a Small Group of Faithful Women Exposed Abuse, Brought Down Powerful Pastors, and Ignited an Evangelical Reckoning.

Stankorb and I discussed the role of the internet in exposing abuse in evangelical communities, the Quiverfull Movement, and how sexual and physical abuse became normalized in certain evangelical communities, but she covers many more topics in her recent best-seller.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: In Disobedient Women, you interviewed different women speaking out against high-control religious environments. What was that like, as a woman, to investigate this?

Sarah Stankorb: I grew up very faithful, but it was a very middle of the road Protestant kind of faith. The Quiverfull Movement was my first look into this world and it was shocking. It was like falling through a rabbit hole into another world. Eventually, I started to understand there’s a web of shared influence that upholds each individual minister’s authority. That’s how you build a worldview.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: The Quiverfull movement was popularized by the Duggars with their TLC show and was described in the documentary, Shiny Happy People. Can you discuss how women and children are uniquely harmed in this environment?

Sarah Stankorb: The basic premise is that you are to create a full quiver for the army of God and the children are the arrows in that quiver. Another component is that you must trust God and the children are blessings. In an environment like that, very frequently, you’re having six, seven, eight, nine, twelve children. You’re often also part of a community where homeschooling is understood as necessary within the family. So add that into an already overwhelmed woman whose body usually does not have time to heal between pregnancies and a house full of children the responsibility of educating them… the mom is simply too tired or pregnant or nursing to actually provide an education across six, seven, nine different grades of children.

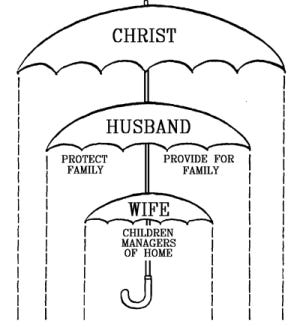

In that environment the eldest daughter usually becomes kind of an assistant mother. In that role, you have young girls taking on the responsibilities of helping raise all these other children. The weight of it does not fall evenly by any means. The male headship over the family is locked in. And so you have a mother who’s taking on all these children, usually home with them all day, trying to feed them, and keep the house running, and depending on the daughter. Girls growing up in these families learn that this is their role, and that if they are to please God, they will do exactly the same thing. They will have as many children as possible. When they’re ready to move out from under their father’s authority, they move unto under their husband’s authority.

There’s no gap in between for them to stand on their own, and for boys, they absorb those lessons just as much that they’re the authority figure, and they’re preparing for when they will be the authority over their wives.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: Can you discuss the sexual abuse scandal involving the Institute of Basic Life Principles, the fundamentalist ministry which purportedly provided instruction on how to find success in life by living according to biblical principles?

Sarah Stankorb: IBLP was founded by Bill Gothard, who developed an approach raising youth, and then created a homeschooling curriculum and also conferences where families would meet, tens of thousands of people, a homeschooling convention. And there you have access to even more of Bill Gothard’s material, and you see other families living in the ways of Gothard, encouraged to have lots and lots of babies.

People think about the Duggar family when they think about IBLP, but Gothard started training centers all around the country and around the world. Youth would be tapped to either go to those training centers or it was a reformatory sort of environment for them.

Then from there, either from the conferences or at a training center, Gothard would meet a young woman, and offered to have them come work with him at headquarters outside of Chicago. These were often young women, girls who have been raised in families with lots of children, homeschooled, many did not know how basic human reproduction worked.

What I’ve found in my reporting, and what has been shared online now for years, is that Gothard would choose one of these young women. He would spend time with her. He would invite her into his office. He would pray with her. It might start with holding hands, maybe touching her legs, putting his arm around her. This might lead to him doing things like rubbing his lips all over her face and neck. He would take off his shoes and rub his sock feet up and down their legs. There’s a lot to do with his sock feet. And these are young women who certainly didn’t understand sexual harassment, who were raised to revere him.

Up until folks started talking about it on the internet, people would say “He’s an old man. He doesn’t understand he’s making people uncomfortable.” But the allegations became more extreme.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: I remember back in 2014 being furious when that scandal broke. Can you talk about the role of the internet in exposing abuse in evangelical communities?

Sarah Stankorb: Bill Gothard is a great example. There’s a website called Recovering Grace, for former ATI homeschooled kids to talk about what life is really like. All of them were shiny and happy as the series says.

But then there was a story about sexual abuse at home. From there, other stories started to come in, and stories about sexual harassment, and other allegations of inappropriate touching involving Bill Gothard started to pour in. What’s interesting to me talking to people who grew up this way, following Bill Gothard, going to the conferences, maybe being groomed by him and having these experiences, is the validation they felt when they read another person’s story online.

It also helped them to understand they were not alone. I think for a lot of survivors, that feeling of solitude is what helps keep you silent. Knowing they were part of a legion of people who had had these experiences, it magnified the sense of injustice and gave them reason to speak up.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: That brings up another question. Can you discuss how child abuse came to play a central role in indoctrinating children in many Christian families?

Sarah Stankorb: Yes. I gave the example of one young person Eleanor Skelton, who had shared their story on Homeschoolers Anonymous.

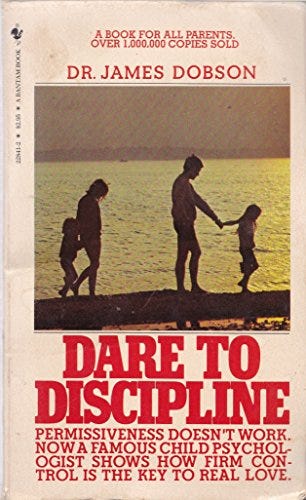

In Eleanor’s case, it was books written by Dobson that taught that it was a parent’s responsibility to teach their child how to be godly and to listen to authority. The alternative to that is corporal punishment. There are some books that are careful to spell out— you spank only with an implement. Hands are for loving. I’ve interviewed too many people on the other side of being hit with all manner of things, anything from little switches that they had to cut out from the trees themselves, wooden spoons, those pizza lifting boards that you just grab, all to impose submission on children.

For a child, when the people who are supposed to make you feel safe can also be the people who cause you pain, if you question, say for instance a pastor who molests you, you understand in a deep and abiding way that there is a severe punishment for speaking up and that you speaking up is wrong. It warps what I think most of us would want from our children, which is to ask for help and the question of an authority figure that’s hurting them. Instead it creates a system of silence that can be very devastating. In Eleanor’s case it took years and years of therapy and work to be able to talk about very plainly and say it for what it was.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: This past week Donald Trump, who has been accused of sexual assault by more than 20 women, won the caucus in Iowa. His greatest support since 2016, has been from white evangelicals. Can you discuss his appeal for those not in the faith?

Sarah Stankorb: I don’t think there’s just one answer. The first time around, the 2016 election, I think it was a mix of a strongman sort of mentality. The promise of Supreme Court justices that would end Roe was an enormous component. We’re also including people who are part of the new Apostolic Reformation, which dwells quite a bit in the world of prophecy, that held on to prophecies about Donald Trump and really did see him as living out what God was promising for the country, to take it back for Christianity, which links it in with Christian nationalism.

But a lot of the people I’ve interviewed, and many who did count themselves as evangelicals up through 2016 , women who still had a lot of faith in their church leaders, as more abuse stories in the church came out, they expected that to be confronted.

When Donald Trump was so popular and so many allegations surfaced against him, for millions of young women raised to be pure, told that keeping their virginity was their highest goal, that it was the greatest gift they could give their husbands. and to see the allegations against Trump not taken seriously by their church leaders, I think that did pull many women women out of the church. What we have left is a population that is able to be tolerant of that. There is a segment that it’s kind of like this John Wayne, Christian masculinity thing, where we’re in a cultural war.

Like, “yeah, we won on abortion.” Now, the culture war is going after trans kids, and we have to win the culture war. We’re claiming this country for Christ, and I think when you compare someone like Biden, who is a Christian, to someone like Trump, when you have that culture war mentality, Trump is a far more attractive leader because he’s willing to fight.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: Over the past decade, women have ignited evangelical reckoning, but we’re also seeing this huge backlash enacted in the Supreme Court, with Roe, with separation of church and state being eroded. Where do you see things going from here?

Sarah Stankorb: Honestly, I’m not positive. Even just the period of the internet that I covered, a lot of it has changed. It’s more diffuse now. Twitter’s imploded. Blogs are what they are. A lot of people have moved over to TikTok. There’s a wider breadth of folks talking. It also creates more little segments for people to fall into.

I think it makes it more difficult to unify and organize together. I also think that the folks in leadership now in a lot of these ministries have learned the lesson of internet mobilization. They have their own internet mobilization teams, so when there is a story that surfaces, they can rally all of their friends to try to fight back against it.

What I will add, though, is I’ve talked to so many women who were raised to submit to people who ultimately showed themselves to be false prophets, and who dared so much by speaking out. There is a model for people who might be afraid, to be able to rally together and fight.